The Semiconductor Construction Labour Conundrum

Written by So and so

Fig 1: Projected Fab Construction starts: Source: World Fab Forecast Report, SEMI

In 2021, the cracks in the Semiconductor Global supply chain were exposed and the dependency of several industries and economies on the supply of semiconductors came to the fore. In response, the semiconductor industry has reacted to the announcements of the construction of several Global Mega projects to increase the capacity of semiconductor projects. In 2021, over $130 billion is to be invested by Intel, TSMC, and GlobalFoundries alone, with further billions being invested by Micron, Samsung, Infineon, and others. These investments plan to double the global capacity of semiconductors within the next 5 years.

While the capital investment will be made available to facilitate the funding of these projects, serious consideration of construction processes, systems and availability of talented labour must be considered.

Fig 2 : Source: BCG report Government incentives and US competitiveness in Semiconductor Manufacturing.

In a 2020 report by the Boston consulting group, Access to Talent was highlighted as a high importance consideration when selecting a location for a new fab. While this report focused on the Talent to Manage a fully operational fabrication facility, the same consideration needs to be given to design and construction talent to build these facilities.

A 2020 survey completed by the Association of General Contractors of America indicated that 81% of 956 respondents were having difficulty in filling open positions. 72% of respondents were concerned about worker quality.

Construction remains a labour-intensive industry with projects of the scale outlined by the main global suppliers requiring between three and ten thousand construction workers for the duration of each project.

Therefore, delivery of these projects will be at risk on two fronts due to labour requirements. One, the availability of skilled labour and two, because construction productivity remains extremely poor. While other industries are improving their productivity curves via the introduction of technology, improved processes and continuous improvement methodologies, the construction industry is actually dis-improving with productivity declining year on year since measurement began in the 1950’s.

To plan for success, clients will need to adapt their existing processes to both improve productivity and source & upskill resources to deliver their projects. The good news is that there are readily available construction productivity improvement processes.

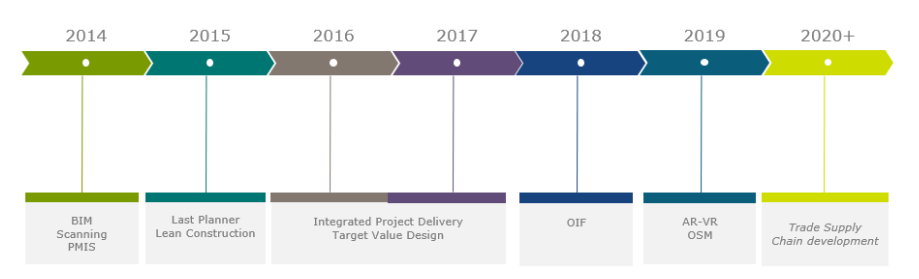

Fig 3: Implementation of Industry Standard Construction Productivity processes. Source DPS Engineering

The first construction productivity curve.

The application of lean principles to construction was introduced as early as 1992 by Koskela’s paper ‘Application of the new production philosophy to Construction’. Koskela was one of the first to link the flow of manufacturing process to that of construction and believed that the implementation of Process based improvements could be applied to the construction industry.

The advancement and adoption of Lean principles took an additional step with the breakthrough work of Howell and Ballard in their 1998 paper ‘Implementing lean Construction’, outlining actions which paved the way for the development of the Lean Construction Institute (LCI). The LCI is now a global community of lean practitioners dedicated to the improvement of Construction via the application of lean principles and processes.

The adoption of Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) contracts, the development of Target Value Design (TVD), the introduction of Building information Modelling (BIM) and the development of the Last Planner System (LPS) have been deemed as the breakthrough intervention systems for construction projects and have shown promising results in several individual projects.

The issue here is not the lack of processes and systems available to improve construction productivity the issue is the ownership, adoption and standardisation of these processes into the client’s global construction processes.

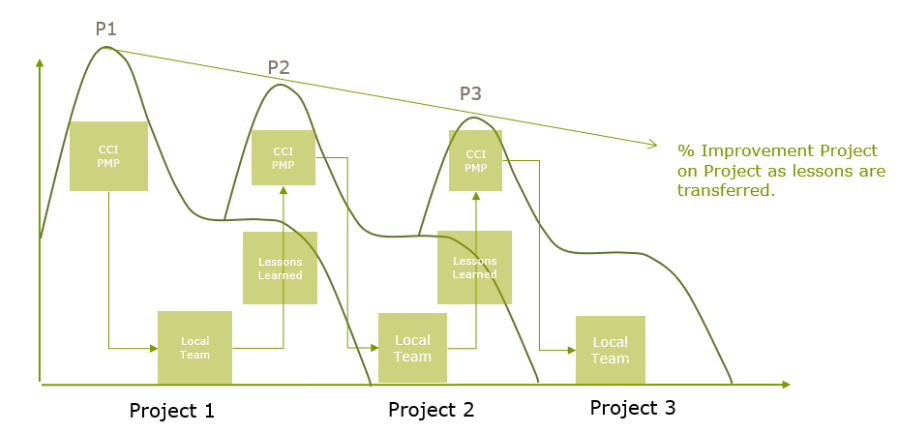

Fig 4: Continuous construction improvement framework. Source: DPS Engineering

The second curve, What’s next?

The construction industry will need a ‘second curve’ to continue improving construction productivity.

Client are seeking continuous construction improvement from project to project with the expectation that improved schedule and reduced costs can be achieved as they move from project to project.

As well as improving the transfer of productivity improvements between project, clients will now need to focus on how they will develop their labour and materials supply chain capabilities. This will require clients to change their processes to ensure that the right suppliers are chosen for scopes of work and that time can be spent with these suppliers to help them preparing and upskilling for future projects. It will also require suppliers to change their frameworks to meet the demands of future projects.

Suppliers will need to embrace future construction technologies such as offsite manufacturing (OSM), digital twinning, productivity improvement measures such as the LPS system and skills development programs for their own supply chain. Suppliers will need to stratagise how they will fit into the larger requirement of these projects in the future and will to determine if the need to focus their business model on becoming specialists or generalists.

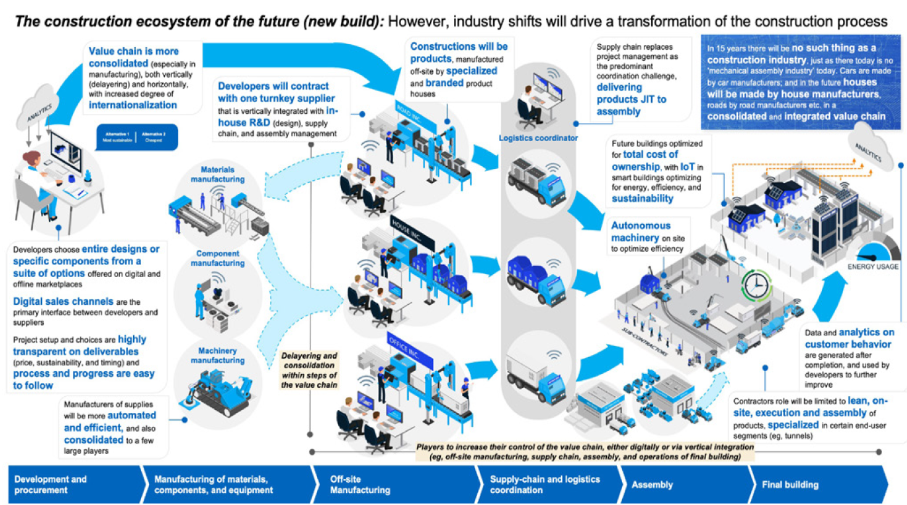

In a recent McKinsey report (the next normal in construction)it was predicted that the construction industry would cease to exist in it’s current form with the next 15 years and would move towards a construction manufacturing format.

Fig 4: The construction ecosystem of the Future. Source: McKinsey Report: The next Normal in construction

All stakeholders in the current construction supply chain will be impacted and the supply chain will need to shift it’s expertise and processes to align with this new format. Clients will push their supply chain to develop modules, pod or standard installation details (SIDs) in order to meet the time to market constraints. While the supply chain will need to change to meet this new reality, Clients need to understand that they also have a significant role in this transition. Simply put, the change will not occur unless the client sets the direction and in order to do this the client-supplier relationship for construction projects will need to change.

Client enabling activities should include the development of longer term contractorial frameworks to enable suppliers to be involved in planning and design requirements but more importantly to build and maintain the expertise required to deliver these projects.

The more advanced clients could look to implement a supply chain development program like processes adapted in the manufacturing industry which develops long term relationships with suppliers but also collaborative continuous improvement activities to ensure quality and supply is not impacted. These strategic partner relationships extends throughout all tiers of the supply chain and is sponsored and supported by the client. We can return to lessons from Toyota to see how the development of supply chain partners can lead to success for clients. Toyota’s Jishuken process embeds Toyota personnel into the suppliers facilities (and allows suppliers to work with Toyota) in order to ensure that both the supplier and Toyota get what they need. Clients requiring large project could look at similar processes to empower and align with their supply chain in a collaborative process for the mutual benefit of both.

The ability to deliver upcoming large projects will be constrained by the availability of skilled construction labour availability. The global construction industry is moving towards offsite manufacturing as one solution to this constraint. Clients will need to embrace this transition and understand that they have a key role in designing the solution. Clients need to proactively engage in their own internal improvement process but also take a leadership role in the development of their supply chain partners.

Richard Casey is the operation manager for the DPS Program development group

(PDG). PDG focuses on the design and implementation of programs to improve

project productivity and cost reduction for DPS clients.